Microbe-assisted mining

Critical minerals power modern technology and Canada’s clean-energy transition. Global demand is soaring, creating major economic opportunities for Canada – but mining must be done in a way that is sustainable for communities and the environment.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) are working with partners to find nature-forward solutions and create spinoff companies to put research into action. One of these ways is by enlisting the help of tiny yet titanic organisms: microbes.

Microbes – and microbiomes, the communities they live in – are sensitive to environmental changes, meaning that they could provide critical clues to ecosystem health. In mining, they can also support more sustainable mineral extraction and help in restoring ecosystems. The complexity of microbiomes, however, makes targeted deployment challenging.

"The philosophy guiding this collaboration is to create a sample-to-solutions pipeline, where data can serve as a starting point for maximizing opportunities and addressing challenges. We’re telling our partners, ‘You can use this knowledge to improve your entire life cycle – all the way from exploration to mine closure.’"-Steven Hallam, Professor, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of British Columbia

The ability to take a census of microbes at a mine can prove invaluable in meeting this challenge. Mapping microbiomes at mines, supplemented with available knowledge of “the variations of the geology and differences in the physical and chemical properties of the environment, leads to a better understanding of microbial community interactions and how they can be leveraged,” for example, for the development of sustainable biomining and bioremediation strategies, says Steven Hallam, a professor in UBC’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

From actionable insights to commercial application

Research from Dr. Hallam’s lab contributed to the founding of nPhyla Technologies, a spinoff company built from the Mining Microbiome Analytics Platform (M-MAP).

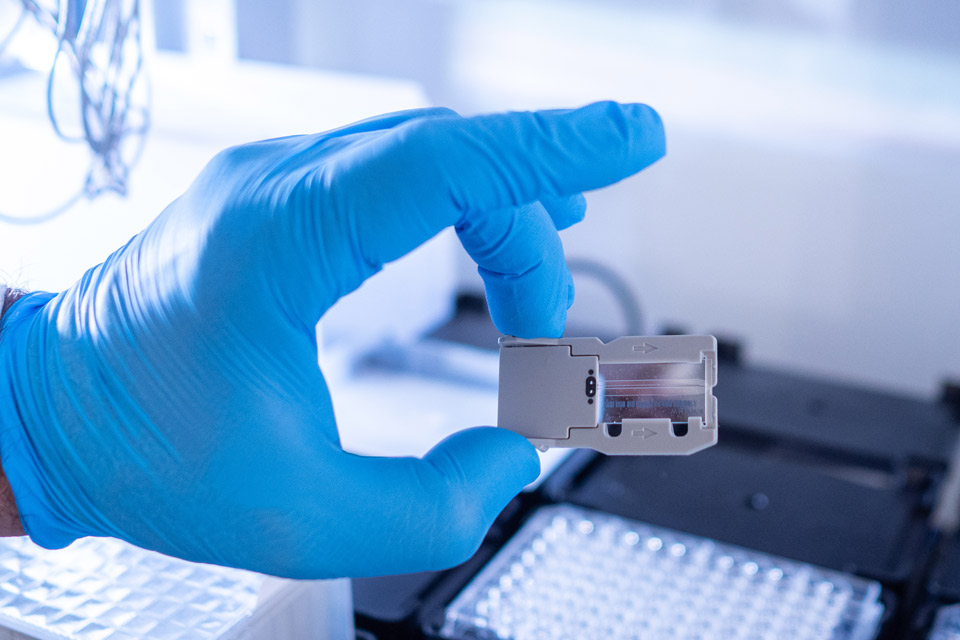

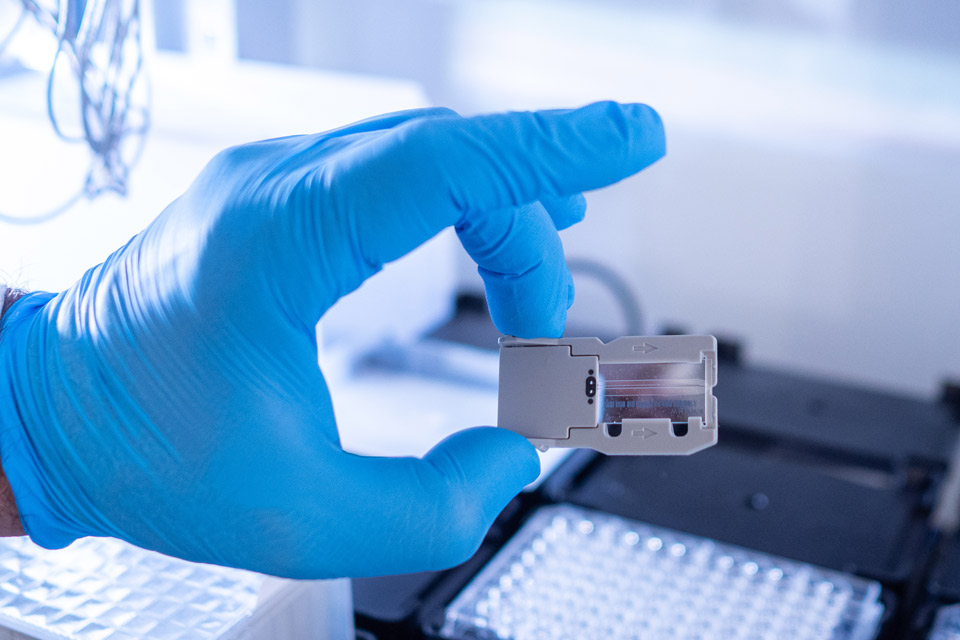

M-MAP uses genomic sequencing and computational analyses to extract information about microbial communities. It was developed by bringing together experts from UBC and industry through Canada’s digital technology supercluster (now known as DIGITAL).

“The philosophy guiding this collaboration,” explains Dr. Hallam, “is to create a sample-to-solutions pipeline, where data can serve as a starting point for maximizing opportunities and addressing challenges. We’re telling our partners, ‘You can use this knowledge to improve your entire life cycle – all the way from exploration to mine closure.’”

The focus on ecosystem health is also valuable when engaging with communities, Dr. Hallam notes. “It can help industry and communities identify pain points and address them in ways that affect outcomes in a more positive way. Any solution needs to be both socially acceptable and scalable at the level industry requires.”

A ‘golden moment’ reflecting excellence and collaboration

The complexity of the undertaking requires interdisciplinary collaboration, a hallmark of UBC’s Bradshaw Research Institute for Minerals and Mining (BRIMM), a founding supporter of M-MAP, says John Steen, BRIMM’s director and an associate professor in the Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering. “BRIMM doesn’t support projects unless they’re interdisciplinary. We need to bring researchers from different faculties and departments together to work on projects that address industry challenges.”

UBC is uniquely positioned for such investigations with expertise in “research and development in the mining sector for over 100 years,” explains Dr. Steen. “We have numerous departments and units across campus – including BRIMM, the Keevil Institute, the Mineral Deposit Research Unit, and the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences – working collaboratively with mining and mining services, including major mining companies.”

Recently, UBC was one of five leading international universities, and the only Canadian institution, invited to join the Rio Tinto Centre for Future Materials. The centre’s ambition is to “accelerate the development of new sustainable techniques and technologies required to deliver the materials necessary for the energy transition.”

“UBC is having a golden moment,” says Dr. Steen, who envisions the university as advancing Canada’s leadership by building on its strengths and values.

“With abundant resources, effective regulatory regimes and respected companies, Canada has a chance to lead, especially in environmental and social responsibility,” he adds. “The goal is to also become a leader in mining technology, so we’re not just exporting raw materials but technology solutions to mining challenges.”

Research-powered practical solutions

Research activities at UBC support a range of solutions, for example, by “looking at alternative ways to mine copper from volcanic brine. We’re also working on the recovery of metals from waste streams and on increasing resource efficiency,” says Dr. Steen, who adds that startups like nPhyla illustrate how to take ideas to impact.

About the transition from platform service M-MAP to nPhyla, a commercial enterprise, Dr. Hallam says, “The ultimate goal of our DIGITAL project was to move with intentionality from capturing data and building data architecture to working directly with clients on biodiversity monitoring and microbial-based solutions development for the resource extraction industry.”

"The goal is to also become a leader in mining technology, so we’re not just exporting raw materials but technology solutions to mining challenges." -John Steen, Director of the Bradshaw Research Institute for Minerals and Mining

Industry participation was – and continues to be – crucial for success, he says. “Working on the digital resource, we realized that gaining a data-driven perspective depended on having thousands and thousands of samples. This meant co-ordinating field campaigns with mining partners.”

The analyses of these samples shed light on microbial diversity at the individual, population and community levels of biological organization and provided critical information about potential metabolic functions, Dr. Hallam explains.

Looking forward, this information can be used to isolate or enrich micro-organisms, enzymes or pathways to improve mineral extraction, stabilize mine tailings, remove contaminants from waste streams, or monitor biodiversity during land restoration and mine closure, among a host of other applications that reduce the environmental impact of mining operations.

Beyond providing the mining industry with a data-driven approach, the research can also benefit “the whole ecosystem of companies that have different interests and different capabilities that coalesce around such processes,” he says. “Understanding microbial communities on mine sites – and how they can be harnessed – can inspire a new way of thinking about our relationship with nature that informs new forms of industrial symbiosis within the mining sector.”

This article was first published on November 21, 2025, in the Excellence in research and innovation special feature in The Globe and Mail, produced by Randall Anthony Communications.