“There’s a real untapped need here, as there is currently only one mechanical heart valve available for children,” he says.

- Program:

- Campus: Okanagan

Thanks to the work of Dylan Goode, we are one step closer to being able to offer people who require heart valve replacement surgery a better-performing and longer-lasting heart valve.

Over 14,000 people in Canada require heart valve replacement surgery each year to replace damaged or faulty valves with a biological valve (from a human donor or a cow or pig) or a mechanical valve.

This life-saving surgery comes with its own complications – while tissue valves offer excellent performance, they tend to wear out over time, requiring subsequent and potentially risky surgery. Mechanical valves are great in terms of longevity, but they require people to take anticoagulants to prevent blood clots.

UBC post-doctorate fellow Dr. Goode is at the forefront of research on designing a new valve that combines the best of both current options.

He completed his master’s and doctoral degrees under the supervision of Dr. Hadi Mohammadi at UBC’s Heart Valve Performance Laboratory where he focused on designing and testing innovative – and potentially life-changing – heart valve designs.

Dylan Goode's Profile Dr. Hadi Mohammadi

UBC’s Heart Valve Performance Laboratory

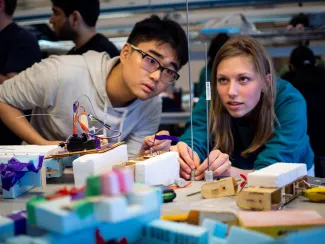

A hands-on approach

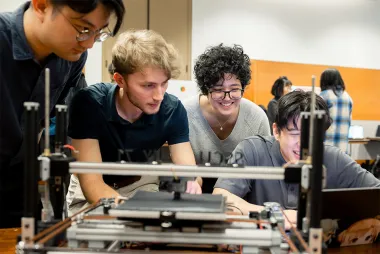

Dr. Goode’s research brings together many different areas of engineering, medicine and science and requires him to be extremely skilled in all aspects of the engineering design cycle, from scoping out problems through to identifying solutions, developing and testing solutions, and iterating and finetuning.

“I went from designing the valve on my laptop in SolidWorks, to creating the code needed to fabricate the valve using the CNC in our lab. I then did the sanding and post-processing to put it together for testing,” he says.

He rigged up the lab’s heart simulator, designed by Vivitro Labs, to test various valve designs. The research he completed for his dissertation shows that the proposed valve has “native-like performance during opening and closing phases, supporting the case for negating anticoagulation therapy.”

Dr. Goode’s path to biomedical engineering

Although Dr. Goode has designed, fabricated and tested what could become the next generation of heart valve, he says that his path to biomedical engineering was something he would not have predicted when he was a high school student.

He didn’t go to university immediately after Grade 12, choosing instead to work in trade-related fields for a few years.

He says he “took a leap faith” to try out engineering because of his strong interest in mechanics and hands-on projects. And while he originally thought he might want to work in clean energy, a fourth-year elective in biomedical engineering changed his plans.

“I just loved this course, which was taught by Dr. Mohammadi,” he says. “There was a new topic almost every lecture, and the students were responsible for researching innovations in the field and preparing presentations on them. My partner and I investigated the transcatheter aortic valve, which was the start of my fascination with how biomedical engineering can have an impact on human health.”

Watch the talk we had with Dr. Goode (starts at 11:17):

It was a pivotal course for Dr. Goode in other ways, too. Although he hadn’t seriously considered doing a master’s before this point, he asked Dr. Mohammadi if he would take him on as a graduate student.

Dr. Goode’s master’s degree investigated different design concepts for heart valves, and he built on this initial research in his PhD, which he completed in July 2024 (read the abstract of his dissertation).

He’s now the manager of the Heart Valve Performance Laboratory and is a post-doctoral fellow conducting research on a wearable device to help people with Parkinson’s disease control their tremors.

He’s also collaborating with Dr. Ryan Flannigan, a researcher at UBC Vancouver, who is developing soft robotics to address erectile dysfunction. When he has some spare time, Dr. Goode also continues to advance research on the heart valve.

Thoughts on engineering research

Looking back on his own journey in engineering, Dr. Goode has advice for others who are exploring their options.

“You don’t have to have the end game planned out,” he says. “When I was in high school, I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to do well in engineering.

When I was in undergrad, it wasn’t until fourth year that I realized I would want to carry on to do a master’s or PhD. Just keep working on trying to better yourself. Try your hardest and focus on what’s in front of you rather than stressing about what might be 10 years into the future.”

He says he particularly loves the research process and being able to explore and test solutions. “Research allows me to deeply understand an issue and then have the freedom to create my own solution,” he says.

“It’s incredibly rewarding to develop something from the ground up, to work through the engineering process, and to test and reiterate. Its also very rewarding to write research articles and get them published and accepted by the scientific community.

"I just love the process of seeing an idea become an actual, tangible solution that could make a difference in people’s lives.”